By Angela Papoutsoglou

Introduction

According to the SaferSpaces Organization, a community-run platform for communal safety and violence prevention practitioners in South Africa, “Public spaces are created and maintained for citizens. They are owned by the public, serve the public good and promote social cohesion. By definition they are accessible to all citizens, regardless of their income and personal circumstances” (1). Public spaces serve as locations to interact with others, socialize, and affirm residents’ shared rights to their city. “Public space is central to the notion of a livable and human environment… and can become the ideal platform for building a sense of community and to move on to even more ambitious collective goals” (SaferSpaces 1). Public spaces are an essential component to any city, and they always have been.

Though public spaces have always played a key role in urban areas, their functions have shifted throughout history accordingly. Their functions and appearances also vary according to the geographic areas they are in, as they are serving specific populations of people. In Medieval times, public spaces served to promote human contact in Europe (Herzog). In the Renaissance, these spaces “conveyed aesthetic beauty,” (Herzog 8) particularly in European cities. Preindustrial European cities’ public spaces “had multiple functions—water collection, news gathering, [and] political expression. Daily use of public space brought strangers together in a space where appearance defined order” (Herzog 9). In the midst of Industrialization periods, “space lost earlier meanings and became merely a domain for circulation” (Herzog 8). Specifically in European cities, public spaces, or plazas, “were the spaces where citizens experienced their identity by engaging in politics, entertainment, or social gossip” (Herzog 10). The connection between public space in urban areas and sense of place or identity “can be traced to the public plaza, whose evolution over the centuries reveals varying cultural expressions at different points in time of the need for public life in cities” (Herzog 13). Sensibly, as these places are for the public, they accommodate to the public’s ever-changing needs and values, which they have evidently done throughout history.

Public space is relevant to all communities around the globe, but this article will focus specifically on Italy.

The birth of the public space in Italy likely traces back to the Roman forum. The forum was “a site of commerce, political discourse, the administration of justice, and dissemination of news” (Herzog 14). “Shops were set up on the forum to teach language and rhetoric as part of commercial life… There were public-speaking daises on the Roman squares for engaging in political discussion. Public controversy could be aired here… Much information was dispensed in the forum: election posters, sale contracts, wills, adoption notices. It was, in short, a media center” (Herzog 14). The public aggregated towards public squares/plazas “on a daily basis, and a sense of collective destiny and community prevailed in public life” (Herzog 14).

Today, public spaces are still extremely relevant in Italy, some of which are famous tourist attractions. Public spaces in Italy such as piazzas, parks, and architecture, in addition to public artwork, contribute to the formation and solidification of a communal, local, and/or national identity.

The Piazza

The italian piazza is an integral component of every italian city. The piazza “is often described as the ‘salotto urbano all’aperto’ (outdoor living room)” (Solly 85). “A piazza is defined physically as a large open space surrounded by (public, residential and commercial) buildings, and socially as a meeting place for people, providing them with a sense of community, identity and a set of resources for everyday life” (Solly 85). The intentional function of piazzas varies among individual piazzas, depending on when they were constructed, where they are located, what surrounds them, and their relative location to neighboring residents.

Piazza della Vittoria, Piazza Mazzini, and Piazza Domenicani were constructed in Bolzano, a city in the Trentino-Alto Adige region of Italy. This territory was formerly controlled by Austria, so its architecture and culture were heavily Austrian-influenced. These piazzas were constructed during the fascist period in Italy, “when the government brought this former Austrian territory under its control. The planning approach was linked to fascist ideology and domination, using the rationalist architecture” (Solly 82) to conform the territory to the fascist-style (inspired by classical Roman art) Italy that Mussolini idealized. “The development concept for the city was that of expansion and growth through [italianization], which included the destruction of the city’s Austrian-influenced buildings and replacement with rationalist architecture” (Solly 82). The new architecture put in place “was intended to discipline and subordinate” (Solly 82) the residents of the area. It is clear that one of the tactics used by the italian fascist regime was converting any foreign or oppositional influences in Italian territories into purely Roman. This conveys the cultural relevance and impact that public urban elements have on the community. Through the shift to fascist-style architecture may not have transformed the residents of Bolzano’s cultural identity, it was surely an attempt at doing so, which highlights the influence of public spaces on communal and cultural identities. Furthermore, the implementation of specific political symbols, monuments, or architectural styles in public spaces enforces the particular political ideology on the community it stands within, which influences the communal identities of the people.

Retrieved from https://www.weinstrasse.com/en/highlights/town-of-bolzano/historical-places/piazza-della-vittoria-victory-square/

Retrieved from https://foursquare.com/v/piazza-mazzini/5194f8ea498ec8544c119265

Retrieved from https://www.weinstrasse.com/en/highlights/town-of-bolzano/historical-places/piazza-domenicani-domenican-square/

Despite the history of these piazzas, or the history they were covering up for that matter, they are still used frequently by residents today. For example, there is no evening that one cannot observe people experiencing their nightly passeggiata, or walk/stroll amidst these squares (Solly 85). This is a common cultural practice in all of Italy, and even other European countries. Piazza Mazzini is converted into a farmer’s market every Tuesday for the local residents to acquire locally-grown produce. Piazza della Vittoria is used by people of all ages for various reasons. Children “ride their bikes, roller skate, or even play cricket… The park area is used for rest, relaxation and for socializing by those in search of companionship. The park is used more intensively during the summer months, to obtain relief from the heat. This is particularly the case for the elderly, who go to the park specifically to enjoy coolness and shade, despite there being only one bench that remains in the shade throughout the day” (Solly 86-87). Commonly, caregivers meet their elderly charges here as well (Solly 86-87). According to the residents of neighboring communities, “for those who live close to the piazza, it is a vital space where they can go/ an alternative to being confined to homes without balconies or gardens” (Solly 87-88). Despite the political symbology that these spaces carry, locals in Bolzano still utilize the piazzas on a daily basis, which serves as reminders of their very own culture connected to how they use them.

Finally, in a separate context, “Piazzale dei Cinquecento, the square in Rome once devoted to the memory of Italian soldiers fallen in Africa is, after all, now one of the principal gathering places for immigrants from Africa and Asia” (von Henneberg 75). This square was renamed in memory of the fallen soldiers in the battle of Dogali in 1887. Due to this historical event that took place in Africa, African immigrants in Italy find this piazza as a comforting space to connect with both their italian residence and native culture. It is evident that piazzas are gathering places for communities to interact, experience, teach, and solidify their cultural identities, even if they are not Italian in heritage.

Retrieved from https://foursquare.com/v/piazza-dei-cinquecento/4cb6b2c164998cfa707117a2/photos

Several different ethnic groups present in the area utilize these piazzas harmoniously, and “the very fact that they manage to share this space with little or no indication of tension would suggest evidence of healthy urban citizenship” (Solly 93). This suggests that piazzas generally bring residents together as a community, providing a space that all can feel comfortable using simultaneously and interacting with other community members doing the same. Piazzas not only provide the physical space to embrace one’s culture as an italian resident, but also encourage the intermixing of foreign cultures that are present within the proximity of the space.

Public Art

“From street art to site-specific installations, from poetry to theater up to ‘live’ works, artistic experience, shared with local communities, become instrument[s] to regenerate both the system of relations between people, which supports the definition of community, and the process of interaction between people and built environment” (Onesti 1). As Onesti states, art is a tool that is used to represent cultural values and experiences, which fosters a communal identity among the group(s) it alludes to. This is particularly the case in Italy, as Italian art is famously used to illustrate important historical events. “Through the use of art from the Renaissance, museums and modern Italian society ha[ve] worked to create a unified culture” (Witwer 5). Since this art is available to the public population as well as to tourists, it allows the confirmation and education of italian identity through its art.

Art History and Anthropology expert, Olivia Witwer, explains that “In order to be a successfully unified nation, Italy has needed to find a unifying factor that projects an image of a strong nation who is an irreplaceable world power. Art is one of the most iconic aspects of Italy that draws in tourism and contributes to the nation’s economy. With Italian Renaissance seen as the pinnacle of western civilization, it serves as a stable base for Italy’s cultural identity to develop into its national identity” (7). Italy has struggled to stabilize one national identity due to the variety of nations that have controlled different areas of the peninsula. One aspect of italian culture the peninsula has been able to build its identity upon is its artwork. Witwer further goes on to say that “Viewing artwork by the Grand Masters of Italy is the highlight of a tourist’s travels, and Italy uses this attraction to say that when you view these works of art, you view Italian culture, and therefore Italy” (Witwer 8). This emphasizes the fact that Italy uses its world-renowned art from the past as a symbol of its culture in the present, which it shares with locals and visitors.

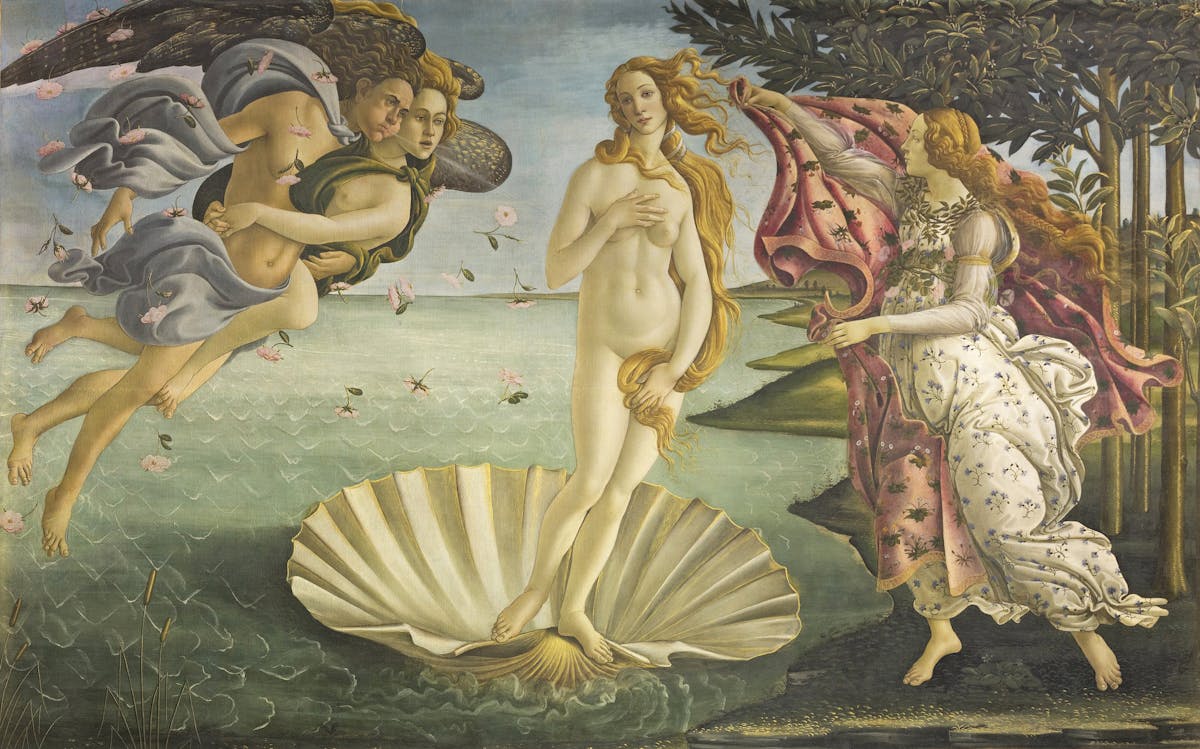

Florence in particular is one of the most influential cities on the Italian cultural identity formed by the arts. Florence “embodies the identity that Italy would want to spread throughout the nation as a historically and culturally significant center, and uses the tourism industry as a way to spread this ideal image of their cultural and national identity” to the rest of the world (Witwer 35). Since Florence was an extremely wealthy city that invested in the arts during the Renaissance, they hold some of the most iconic pieces of art in Italy, and even the world. Two specific pieces of art that reside in Florence greatly contribute to the face of Italian culture: The Birth of Venus by Sandro Botticelli and David by Michelangelo.

Retrieved from https://www.uffizi.it/en/artworks/birth-of-venus

Retrieved from https://www.accademia.org/explore-museum/artworks/michelangelos-david

“The symbolism of David and what he represents for Florence, is a projection that Italy has attempted to adopt for the whole of the nation. By advertising that the work belongs to the nation-state, not just Florence, Italy has worked to create this projection of unity and freedom. The battle between the city of Florence and the nation-state of Italy over the ownership of this iconic work of art shows that the symbolism behind the figure of David is a national symbol that Italy wants to embody. A symbol of strength, freedom, and intelligence, David is the identity of a nation that Italy wants others to view it as” (Witwer 36). The public accessibility to this sculpture promotes the symbology it presents for italian culture to be shared and reinforced to all Italians and foreigners.

Both The Birth of Venus and David serve as representations of Italian culture and “for the glory of Italy. [The artworks] also serv[e] as an advertisement that Italy is united under one culture that is demonstrated through key works of art from the Renaissance. The national identity that Italy attempts to embody comes from the iconic period of the Renaissance as it was large step in society towards modernity and would go on to influence other European nations and cultures. These works have been canonized as the epitome of perfection that is represented through the culture that they present, as the bases for Italian culture” (Witwer 35-36).

Through public museums and art galleries, and the artworks they hold, Italy outwardly defines its cultural identity to both residents and travelers.

Street Art & Public Murals

In general, public art has a considerable positive effect on those who roam the city containing it. Neuroscientist Colin Ellard states “that studies have proven boring cityscapes increase sadness, addiction and disease-related illnesses” (Chow 1). Ellard says that, furthermore, “around lively facades, people ‘pause, look around and absorb their surroundings while in a pleasant state … and with a lively, attentive nervous system’” (Chow 1). “Art integrated throughout a city physically slows [people] down” (Chow 1) in the currently hyperactive world. In fact, people tend to walk half as fast when public art is present in a city than when it is not. Not only is public art beneficial to individuals experiencing it, but also on a larger scale for communities. Anna Onesti states that the appearance/aesthetics of a city’s landscape “increases the feeling of belonging [and] the sense of community” (1) of those who reside there. In addition, Onesti describes that “art develops an attitude of respect care, antithetical to the degradation dynamics that characterize the urban spaces. So, the relationship with artwork becomes an attitude of care towards a heritage which is recognized as a common good. Furthermore, sharing the same experience and the same sense of affection, people pass from feeling extraneous in the city to becoming a member of a community (heritage community) whose members recognize the same landscape as cultural heritage” (1).

In Italy specifically, there are countless examples of art available to the public. This includes the many famous pieces of architecture, but also statues and street art. Street art may not be the first form of art one thinks of when they reference italian art, but it is rooted deep in italian culture and has been used as a tool to improve urban areas.

The italian tradition of street painting, now called street art, dates back to Ancient Rome, “where artists scratched celebrations of esteemed gladiators and diatribes about politicians” (Shaw & Noa 26). As time progressed, street art evolved mainly into voicing “social and political commentary, giving voice to those often unheard” (Shaw & Noa 26). This form of art available to the public, especially to those who live in the area and view it daily, is extremely beneficial to the sense of place that is felt. Author Robert Fleming said that “because it interacts with the environment, the history and relationships that exist in a specific place, public art establishes a sense of place in a particularly powerful way. Creating meaningful relationships and a deeper connection to a place is essential to being invested and involved in one’s community” (Shaw & Noa 26). In fact, Venice directly “attributes its community revitalization in the 1970s to public art” (Shaw & Noa 26). This tactic is being used quite often now to revamp urban areas across the Italian peninsula. One example of this technique was used in Barriera di Milano, which was initially “a gloomy district, with nothing but tall, grey buildings: [street artist] Mills [gave] it a new face that dialogues over the themes of humanity and metropolis. The Barriera di Milano neighborhood thus has become a huge, deep narration, with man as the protagonist” (Scuffietti 1). In Rome, street art with bright colors has been added to specific neighborhoods “considered to be ‘skidding,’” in order to “give new life to” (Cirelli 1) these areas.

Artist: Millo (Francesco Camillo Giorgino)

Retrieved from https://vagabundler.com/italy/streetart-map-turin/corso-palermo-117/

Street art has also been used in Italy to directly portray the country’s cultural values and ideals to share with others. This may act as an educational opportunity for foreigners or reaffirm these ideals within the community itself. For example, after the pandemic, murals representing desire, peace, and unity have become extremely popular in Italy to remind community members that they are not experiencing this difficult time alone. In addition, “At the hospital in Padua[,] one of the most touching murals is a nurse dressed like Wonder Woman, to thank and recognize all the incredible work carried out” (Eco Street Art 1) by healthcare providers in recent years. In Naples, one can find several works of street art by Alice Pasquini that famously value the “representation of women and children” (Cirelli 1). Most influential of all, Via Aldo Moro was completely transformed by the “Walk the Line” project, which implemented “an open-air gallery over [three kilometers] long” (Cirelli 1). The impact of this transformation on the Genovese community, especially those nearby the supporting structures of Via Aldo Moro, is remarkable.

Street Art by Alice Pasquini in Naples, Italy

Retrieved from https://www.alicepasquini.com/alice-portfolio/outdoor

Retrieved from https://creart2-eu.org/activities/creart-street-art-project-in-genoa-walk-the-line/

Though public street art already spreads powerful messages, an even greater addition has been introduced to the art medium. A new “Airlite paint,” created in Italy, is being “used in mural[s] to neutralize pollutants and smog” (Diskin 1). One mural titled Hunting Pollution by Milanese street artist Frederick Massa “is beautiful and improves the air quality of Rome. Covering over 10,000 square feet of a seven-story building, the mural is made entirely of [this] anti-pollution paint, [intending] to raise awareness of environmental problems like global warming and animal extinction” (Diskin 1). The amount of Airlite paint used in this particular mural allows it to produce “the same air-cleansing effect as a forest with 30 trees” (Diskin 1).

Retrieved from https://matadornetwork.com/read/street-art-piece-improves-air-rome/

Author Amy Goodwin summarizes the great impact of murals in her book On the Wall, writing that “‘The true power of murals lies in their local, community impact: to see issues that resonate with real people, the oppressed, the poor, the overworked, [and] the underrepresented. The process, the act of community building and collaboration, the beautification that community murals provide create intangible thread’” (Shaw & Noa 26) to better the populace. On a larger scale, street art can also help teach the younger generations in the area “how their decisions have an impact beyond themselves in a larger context—not only within the piece of art but also within the community” (Shaw & Noa 26). This concept applies to Italy, as these pieces of public art are being taken into educational settings to be analyzed, which will ultimately benefit the future of Italy.

Conclusion

Through several cultural elements like language and food, Italy secures its national identity, but it is profoundly influenced by public spaces and public art. The importance of public spaces in urban areas is inexplainable. Artistic elements, including both pieces available for observation from the streets and those housed in museums, greatly shape the cultural identity that Italians feel and proudly express. In addition, outdoor spaces open to the public help define the way of living for many Italians, which is a large component of their unique cultural identity that they share. The most important public space in italian cities is arguably the piazza, serving as a cultural breeding ground, socialization space, relaxation space, play space for children, navigation point, and even more. The presence of public spaces in urban areas in Italy is crucial in constructing and confirming the community’s, city’s, region’s, or nation’s cultural identity.

Works Cited

Botticelli, Sandro. “The Birth of Venus.” Le Gallerie Degli Uffizi, https://www.uffizi.it/en/artworks/birth-of-venus. Accessed 19 Apr. 2023.

Chow, Rony. “The Impact of Public Art Projects on Human Health.” Polyvision, 28 Feb. 2018, https://polyvision.com/the-impact-of-public-art-projects-on-human-health/.

Cirelli, Cleo. “Street Art in Italy.” Rome and Italy, 17 Sept. 2021, https://www.romeanditaly.com/street-art-in-italy/.

Diskin, Eben. “This Street Art Piece Improves Rome’s Air Quality.” Matador Network, Matador Network, 19 Nov. 2018, https://matadornetwork.com/read/street-art-piece-improves-air-rome/.

“Eco Street Art That Cleans the Air.” Unexpected Italy, 16 June 2022, https://www.unexpected-italy.com/eco-streetart-in-padua/.

Herzog, Lawrence A. Return to the Center: Culture, Public Space, and City Building in a Global Era, 1st ed., University of Texas Press, Austin, TX, 2006, pp. 1–28, https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=VyjL_E2q6UoC&oi=fnd&pg=PR9&dq=public+spaces+and+art+in+Italy+cultural+identity&ots=9gTnmwyCAy&sig=MTEujhJdAJYyDBW3EIn_jT7Mp5g#v=onepage&q&f=false. Accessed 18 Apr. 2023.

“Michelangelo’s David.” Accademia.org, Florence, Italy, 2020, https://www.accademia.org/explore-museum/artworks/michelangelos-david. Accessed 19 Apr. 2023.

Onesti, Anna. “Built Environment, Creativity, Social Art. the Recovery of Public Space as Engine of Human Development.” REGION, vol. 4, no. 3, 5 Sept. 2017, pp. 87–118., https://doi.org/10.18335/region.v4i3.161.

“Public Spaces: More than ‘Just Space’.” SaferSpaces, 2023, https://www.saferspaces.org.za/understand/entry/public-spaces.

Scuffietti, Giulia. “Street Art in Italy, a Brief Overview.” Italcult, 15 Mar. 2016, http://www.italcult.net/street-art-in-italy-a-brief-overview/.

Shaw, Laura, and Mandy Noa. “Using Street Art to Engage Teens in Social Emotional Learning.” Social Work Today, Great Valley Publishing Company, https://www.socialworktoday.com/archive/Winter21p26.shtml.

Solly, Hilary. “Making Public Spaces Public: An Ethnographic Study of Three Piazzas in Bolzano, Italy.” Urbanities, May 2021, https://www.anthrojournal-urbanities.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/8-Solly.pdf.

Von Henneberg, Krystyna Clara. “Monuments, Public Space, and the Memory of Empire in Modern Italy.” History and Memory, vol. 16, no. 1, 2004, pp. 37–85., https://doi.org/10.1353/ham.2004.0003.

Witwer, Olivia. “The Search for an Identity: The Merging of the Past and Present to Form a Future in Italian Culture.” University of Colorado at Boulder, 2017, pp. 1–43.