One phenomena that I am extremely interested in is the way that, throughout history, marginalized people have been seen to participate in their own oppression. It has been proven that women, and other groups, can be conditioned to accept negative messages about themselves and work actively against their own interests, which is why I want to look at how fascism treated women, and how they acted in return. It cannot be denied that women both participated and protested enthusiastically within Italy at the time of the fascist regime, and I am mostly trying to explore how women accepted negative messages about them, and therefore focus on participatory women. I think that one of the most directly related issues here is the economy. While at this time men were considered the driver’s of the economy, women had a stake in it too as consumer’s for their families. I also think World War I is a big factor that shaped women’s responses to fascism. The largest institution concerning this issue is the Italian Fascist government, as it set the rules and norms for women at this time.

Fascism and Feminism at the beginning

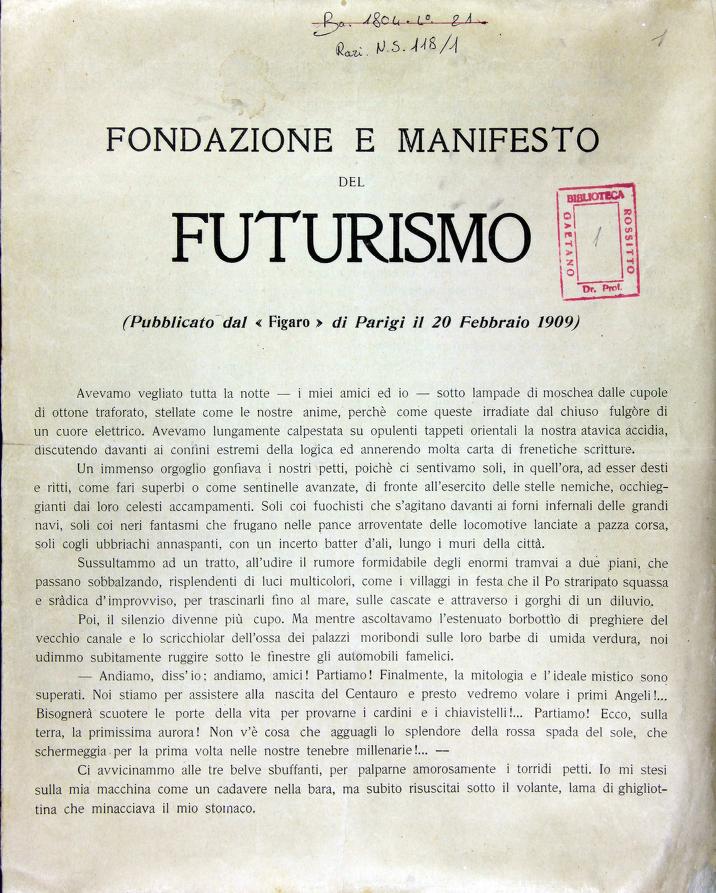

At the beginning of the fascist movement, women and feminist groups had some hope that they would be recognized by the fascists and their fight may be propelled forward. To us, this may sound ridiculous, but at the time groups like the Socialists, Democrats, and even the Catholic Church had associations within their organizations for women, that was supported by a larger feminist movement in Italy (De Grand, 948). While the larger fascist movement had only unimportant women’s groups with little power, the Futurists, who were heavy supporters of the fascist movement, did believe in furthering gender equality and even called for female suffrage and salary equality in their 1918 program (De Grand, 952). The futurists even had some influence on the fascists as the fascist program of 1919 called for full voting rights for women and equal right to hold office” (De Grand, 952). Mussolini knew that, as women were a large part of the population, he needed to appease them in some way. He announced a policy change that would give women equal footing in the party and announced that the government would present a law on women’s suffrage, but neither came to any real fruition (De Grand, 953). Despite these failed promises and overall hostility towards women’s rights by the party as a whole and Mussolini in specific many women and female groups were “drawn by the patriotic rhetoric of the government, were disposed to support the Fascists” (De Grand, 953).

The Effect of World War I

The effect of World War I on Italian women was strong and it prepared women for the coming fascist regime in multiple ways. On the one hand, women had a taste of economic freedom because, as with many wars, a lack of male laborers pushed women into workforces that they were previously not allowed to participate in. At the end of the war these wartime industries were shut down and thousands of women were leaving the employment market after failing to find positions to replace those lost to veterans” (De Grand, 949). Interestingly enough, appeasing veterans was a big reason that women were not allowed to work, as it was expected that women would not push for jobs that were “rightly” for veterans; if they did they could be considered disrespectful of those who fought for Italy (De Grand, 952 – 953). Women’s participation in the workforce also led to hostilities against women because of their perceived “invasion” of male oriented employment, which would later inform policies of the fascist regime (Willson). Women’s employment during the war was essential in shaping women’s positions after the war, as well as the perception of women by the fascists.

World War I also informed women’s position in the fascist regime based on the overall stability, or lack thereof, and state that Italy was left in. World War I left Italy very unstable and impoverished and “the Liberal government asked much of its population but failed to attend to the raised expectations after the war ended” (Belzer, 180). Because of this the women’s movements were susceptible to nationalist propaganda that went against their regular ideas (De Grand, 950) and someone like Mussolini who seemed willing and able to provide stability and improve the nation was an attractive prospect to many women (Belzer, 180).

Youth Organizations

Just like many other dictatorial regimes, fascist education started young, and children of both genders were expected to participate in fascist organizations and learning. Childrens groups were separated by age and gender and for girls they could join the Piccole Italiane from the ages of eight to twelve years and then the Giovani Italiane from ages thirteen to eighteen years old (Willson). These groups participated in exactly the kinds of activities that were expected of a young fascist woman would need to become good fascist wives and mothers such as “domestic science classes and ‘doll-drill’, where they learned child-care techniques to prepare themselves for their future role as wives and mothers” (Willson).

Less expected was the female participation in sports. While it may seem contradictory to the idea that women should be preparing only for motherhood and keeping a family, many middle class young women were able, and even encouraged, to participate in certain sports. The idea behind this was that “graceful, artistic forms of gymnastics” would help young girls stay healthy, which would benefit them in their futures as mothers (Willson).

Women and the Family

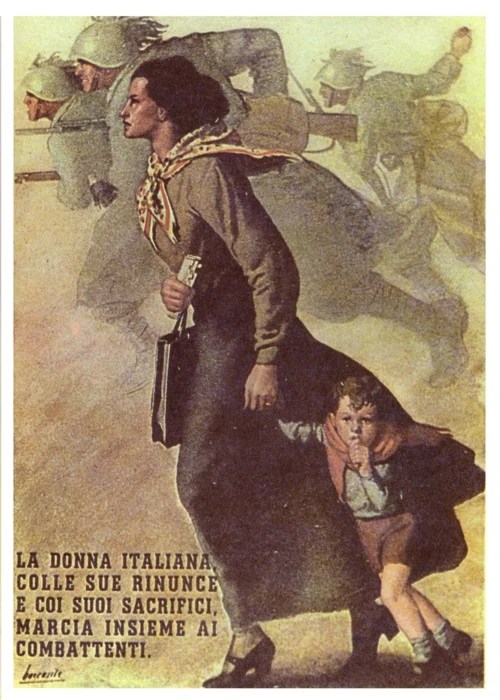

Middle class women’s place in fascist Italy was at home and with a family. A similar message we see in all kinds of nationalist and dictatorial regimes is that women are important because they are raising the next generation of men for the regime. Women were encouraged to see themselves as “agents of history” (Belzer, 183) that were shaping the nation, rather than seeing themselves as subjugated by the laws of the fascist regime. The fascist propaganda told women that they were “responsible for morale” in Italy and at the warfront (Belzer, 183). To fascists, this was the most important responsibility, even if they were allowed to participate in other ways: “Women were brought into the project of nation building because of their unique biological ability to bear children and their societal responsibility to indoctrinate them” (Belzer, 178).

The fascists had many ways to encourage women to prioritize their families and the work of raising the next generation of fascists. The fascists were extremely focused on the problem of a falling birthrate “which they termed the ‘problem of problems’” (Willson). There were government interventions to promote early marriages, motivating married couple to have more children, and even material laws that imposed taxes for failing to wed (Willson). Families with between seven and ten living children received benefits “like free school books, medical care, or priority in certain types of employment” (Willson). Publicity about birth control was banned by the Rocco Code and the only exceptions were for messages that birth control could cause uterine problems or facial hair (De Grand, 958). Anyone deemed to be an “anti-demographic group” (De Grand, 961 – 962) such as gay men or midwives suspected of performing abortions were dealt with criminally and could be sent to confino politico which was a kind of internal exile. While it seems counterproductive to women’s rights, many women accepted this rhetoric and even women’s publications believed that “fascism had done more for women than any liberal regime could have done in the area of syndical rights and welfare” (De Grand, 961 – 962). Many middle class women did see their position as belonging in the household. These women didn’t see their relegation to the home as subjugation, but rather as an important position that it could be an honor to hold.

One thing that I found very interesting is the way that Mussolini fit into this family dynamic as well. Many women saw him as a father figure to the movement, or even a father figure more personally. Women would call him “our father, guardian angel and head of our great family that is Italy” (Belzer, 185). Women would even write to Mussolini asking for favors and advice. This shows that women felt as if they did belong to the state and considered themselves to be his constituents just as much as men.

Female Employment

An important aspect of the participation of women in this regime is what employment opportunities they did and did not have. To start, we have to understand that when it comes to employment of women, there was a certain message about women, but it was not always economically feasible. Poorer women could not be prohibited from working because their families simply would not have enough income if the mothers were not working (Willson). Therefore, the idea that women should be housewives was really only able to be carried out by middle and higher class women. Middle class women who wanted to work had few prospects. Women’s publications had articles about what kind of work was suitable for women and that work was “an extension of the home, either in the form of domestic work, rural crafts or teaching” (De Grand, 958). Even in careers like teaching, however, that could be considered acceptable work for a woman, the regime often made it harder to stay employed. Some legislation allowed for quota-fixing in schools, which limited how many women could be school inspectors (Willson) . The minister of education, Giovanni Gentile, also tried to limit the amount of female teachers in predominantly male schools because he believed that “’women do not have, nor will they ever have, either the moral or mental vigor to teach in those schools which formed the ruling class of the country” (De Grand, 953). This is an exceptionally interesting rationale to me, because it seems to go directly against the rhetoric that women must stay home and raise children because they do have the moral vigor to raise the next generation. While I feel comfortable saying that the main reason women were pushed out of employment, even ones they had been previously relegated to, is misogyny, there was some rationale for the fascists. First, the fascists believed that working was a distraction from having and raising children, and that it “forms an independence and consequent physical and moral habits contrary to child bearing” (De Grand, 958) according to Mussolini. The fascists also believed that women in the workforce caused the poor employment prospects for men, essentially emasculating them (Willson).

Female Participation in the Party

The last aspect of fascist women that I was interested in was the level to which they participated in the party and in what ways. Women’s participation in society was officially limited to ways that supported the fascist party and aligned with fascist messages. An example of this is the way that women’s publications became fashion or family magazines that included excerpts of fascist propaganda and/or Mussolini speeches (De Grand, 955). Women did have a section of the fascist party dedicated to them, called the Fasci Femminili, though they often worked on the demographics campaign (De Grand, 961). The Fasci Femminili grew rapidly, with 100,000 members in 1929 to 750,000 members in 1940 and even over one million members in 1942 (Willson). Women’s participation was especially strong in supporting the war in Ethiopia. Women were expected to offer their gold items, such as their wedding rings to the state, in order to finance the war and colonial efforts in Ethiopia (De Grand, 961).

Many women participated because they truly were committed to fascism and the goal of the fascist party, but others participated less fervently for reasons such as material incentives, fear, opportunism, or desperation” (Willson). Millions of Italian women did participate in the organizations that were organized for them in the fascist regimes (Willson). These positions gave women duties that could give them a sense of purpose in their life and in the party, as well as giving them the opportunity to make a place for themselves in the public sphere (Willson). Unfortunately for women who chose to participate, these duties and roles were of relatively little importance, often only useful as iconic to the party (Willson). In the following video, this participation can be seen as women walk in a parade overseen by Mussolini. This is a purely iconic parade, and once the women return to their regular positions, they will have none of the power their male counterparts have.

Conclusion

The way that women interacted with and participated in the fascist regime is an extremely important historical topic to look into. History often repeats itself and we have seen women in multiple regimes collaborate and cooperate with their oppressors. In order to prevent the same from happening again we need to understand why it happens. While this essay won’t provide all the answers to these questions, it could help provide a primary exploration into them. Putting oppressive regimes and marginalized people into the appropriate historical context is vital to understanding why people make the choices they do. Overall, I found that many fascist women participated fervently and passionately, while others participated only begrudgingly. Historical factors made it necessary for women to cooperate in order to survive and thrive, and the regime often made it their only choice.

Information Citations

De Grand, Alexander. “Women under Italian Fascism.” The Historical Journal 19, no. 4 (1976): 947–68. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2638244.

Willson, Perry, ‘ Women in Mussolini’s Italy, 1922–1945’, in R. J. B. Bosworth (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Fascism (2010; online edn, Oxford Academic, 18 Sept. 2012), https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199594788.013.0012, accessed 27 Nov. 2022.

Belzer, Allison Scardino. “Italian Fascism and the Donna Fascista .” Essay. In Women and the Great War: Femininity under Fire in Italy. Palgrave Macmillan, 2010

Media Citations

Limited, Alamy. “In Rome, on May 26 or 27, 1939, a Large Parade of Tens of Thousands of Female Fascist Participants Took Place in Front of Mussolini. the Picture Shows Women Shouldering Rifles. They Accompany Their Husbands, Italian Colonial Soldiers, on Their Way to the Colonies. [Automated Translation] Stock Photo.” Alamy. Accessed December 8, 2022. https://www.alamy.com/in-rome-on-may-26-or-27-1939-a-large-parade-of-tens-of-thousands-of-female-fascist-participants-took-place-in-front-of-mussolini-the-picture-shows-women-shouldering-rifles-they-accompany-their-husbands-italian-colonial-soldiers-on-their-way-to-the-colonies-automated-translation-image446963115.html.

“Futurist Constitution and Manifesto.” The Library of Congress. Accessed December 8, 2022. https://www.loc.gov/item/2021667099.

Women’s mobilization for War (Italy). New Articles RSS. (n.d.). Retrieved December 9, 2022, from https://encyclopedia.1914-1918-online.net/article/womens_mobilization_for_war_italy

Members of the Piccole Italiane, an Italian Fascist Youth Group for Girls Aged Eight to 14. Slate . The Slate Group. Accessed November 27, 2022. http://www.slate.com/blogs/atlas_obscura/2014/10/22/colonia_fara_in_chiavari_italy_is_an_abandoned_fascist_youth_camp.html.

Girls Participate in Sports . Getty Images . Getty Images . Accessed November 27, 2022. https://www.gettyimages.ca/detail/news-photo/italy-lombardia-milan-arena-sport-1920-1930-news-photo/1177029218?adppopup=true.

War Propaganda. Galvan Jaqueline WordPress. Accessed November 27, 2022. https://galvanjacqueline.wordpress.com/2016/04/15/gino-boccasile-opticc-5/.

Mussolini Greets Family. History Extra. Immediate Media Company, September 26, 2022. https://www.historyextra.com/period/second-world-war/mussolinis-willing-followers/.

Collection of Valuable Objects in a School. Getty Images. Getty Images. Accessed November 27, 2022. https://www.gettyimages.ca/detail/news-photo/young-school-girls-presenting-to-the-teacher-many-valuable-news-photo/141557680?adppopup=true.

Rivista Delle Famigie . University of Wisconsin – Madison Libraries . Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System. Accessed November 27, 2022. https://exhibits.library.wisc.edu/special-collections/italian-life-under-fascism-selections-from-the-fry-collection/family-life/.

UW-Madison Libraries Exhibits.” Women and Fascism. Accessed December 6, 2022. https://exhibits.library.wisc.edu/special-collections/italian-life-under-fascism-selections-from-the-fry-collection/women-and-fascism/.

Benito Mussolini Reviews Fascist Women Parade at the Piazza Veneaia in Rome, Ital…HD Stock Footage, 2014.