By Scott Biggs,

What is Citizenship?

According to Merriam Webster’s dictionary, someone who is a citizen is “a native or naturalized person who owes allegiance to a government and is entitled to protection from it”, or shortly “a member of a state”. But around the world, the understanding of citizenship exists on a spectrum between a strictly legal relation and a deep cultural commitment. Discussions around the meaning of citizenship often lead to extremely difficult and subjective questions,

Do you need to speak the language of the country to be a citizen?

Do you need to live there and participate in society?

Do you need to have ever been there at all?

What about Ethnicity and religion?

There aren’t easy or consistent answers to these questions. Not because they are bad questions, but because of the vast variety of communities and cultures independently having this discussion. According to the Council of Europe, citizenship has four dimensions:

- Political: citizenship entails a right to participate in state affairs.

- Social: Social knowledge and skills, includes familiarity with society and culture broadly.

- Cultural: Awareness of and participation in shared culture and heritage.

- Economic: Participation in the economy, entails right to work and subsist on your work.

In the United States, you can become a citizen by passing a test after living in the US for some time, this is called the ‘naturalization’ process, or by simply being born in its territory. In Italy the primary path to citizenship is Jure Sanguinis,

Jure Sanguinis: The primary mode of Italian citizenship whereby, “Children under the age of 18 are automatically Italian if one of the parents is an Italian citizen, and their birth certificate is registered with the Italian authorities.”

– Consulate General of Italy, London.

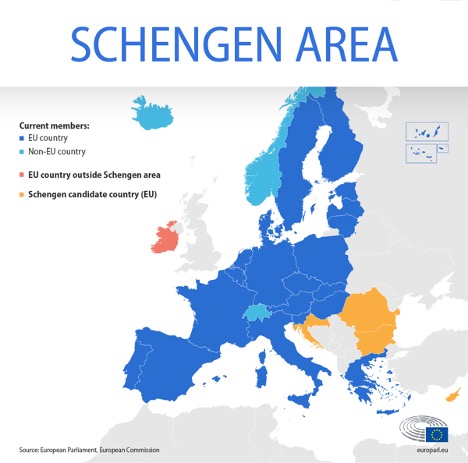

Italian citizenship brings a lot to the table; it makes you a citizen of the European Union (EU) which entails the right to travel, study, live, and work in the EU. As a signer of the Schengen Agreement, Italian citizens have freedom of movement through Schengen members. Italian citizenship also entitles you to access to the Italian social safety net, among other benefits.

The 1948 Rule

The 1948 rule pushes the ‘proving Italian descent’ to it’s limit. So called because of the constitution of the Italian Republic, which entered effect on January 1st, 1948. The 1948 rule allows children born to an Italian mother prior to 1948 to claim Italian citizenship through a lawsuit against the Italian government on the basis of gender discrimination. Prior to the 1948 constitution, women lost their citizenship if they married a non-Italian man while men did not in the same case. In 2009, a court decision retroactively extended this reasoning to cover citizenship claims with claimants born to an Italian mother prior to 1948.

The consequences of the 1948 rule have been profound for Italian communities and their descendants spread across the globe. It has fostered a renewed connection between Italy and its diaspora by creating a legal avenue for those who had long retained a cultural or familial tie to Italy but were previously excluded from formal citizenship recognition. This shift has had cultural and practical implications. By fostering a sense of belonging among individuals of Italian descent by acknowledging and embracing the diverse global community of people with Italian heritage, it has created a space for the descendants of Italian emigrants to engage with their ancestral homeland more easily.

However, at no point in the legal process for reclaiming Italian citizenship is the claimant required to demonstrate any knowledge of the Italian language or culture. Indeed, at no point are they required to go to (or have ever been to) Italy. Unfortunately, this has created a space where some foreigners claiming Italian citizenship view it almost as a thing that can be purchased. This attitude, held by a small but unfortunately vocal minority of those going through the reclamation process, has given the entire mechanism a bad wrap in the public opinion of Italians.

Italians without Citizenship

The 1948 rule also exposes an intuitive consequence of Jure Sanguinis, the legal doctrine for transferring citizenship ‘by blood’, what about people without Italian ancestry?

According to the Consulate General of Italy in London, foreigners born in Italy to stateless parents, or children found abandoned in Italy, may acquire Italian citizenship if lawfully and uninterruptedly resident in Italy from birth up until coming of age. But for many such young people, that requirement is a major bureaucratic obstacle that must be overcome in a short window (as short as a single year).

We children of migration, de facto Italians, who go to school, work, are completely integrated into society – we are victims of discrimination in public sector competitions, at work, in sports because we are Italians with a residency permit. Foreigners in the country in which we were born and/or lived. With all the consequences.

According to Statista, in 2022 about 6.2 million Italians are foreign born. In that same year, about 105 000 (one hundred and five thousand) people arrived in Italy. Some sources put 2023’s estimates around one hundred and fifty thousand. Of the millions of foreign born people living in Italy, at least 1.3 million minors in Italy were in this predicament in 2018. According to EuroNews, that number was still at least one million in 2022. Without citizenship, these young people, many of whom have lived, studied, and worked their entire lives in Italy, cannot vote and are barred from social mobility. As a result, many of these people are participating in a growing political movement to transition the country away from Jure Sanguis and towards Jus Soli (the primary system used by the United States), which would automatically grant citizenship to people born in Italy, regardless of their parents’ citizenship status. However, it is widely considered unlikely that the current government would begin such a transition.

Reflection and Summary

While the 1948 rule has made it easier for many with Italian heritage to reclaim their citizenship, the doctrine of Jure Sanguis that created it prevents millions of young Italians, many of whom have lived and studied in Italy their entire lives, from claiming their own citizenship. Many say this system is unfair. But, at the end of the day, the central question remains,

What is citizenship?

Resources:

Consulate General of Italy in London, Citizenship Services: https://conslondra.esteri.it/en/servizi-consolari-e-visti/servizi-per-il-cittadino-straniero/cittadinanza/

2009 Italian Supreme Court’s 1948 Rule Decision: https://www.mylawyerinitaly.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Italian-Supreme-Court-sentence-n.-4466-of-2009.pdf

Simple 1948 Case Video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3qUm5CujE2w

Population Statistics: https://www.statista.com/statistics/548877/foreign-born-population-of-italy/

Young Immigrants Info: https://www.infomigrants.net/en/post/20200/over-one-million-italians-are-without-citizenship–idos

EURAC Citizens without Citizenship: https://www.eurac.edu/en/blogs/mobile-people-and-diverse-societies/without-citizenship-but-citizens-nevertheless

Council of Europe Citizenship: https://www.coe.int/en/web/compass/citizenship-and-participation

Foreign Policy, Giorgia Meloni and Immigration: https://foreignpolicy.com/2023/10/24/italy-immigration-right-wing-meloni-migrant-crisis/

EuroNews, Italians without Citizenship: https://www.euronews.com/2022/09/21/millions-stuck-in-limbo-trying-to-obtain-italian-citizenship